I have recently enjoyed reading through the Summer 2022 issue of The Hedgehog Review, one of my favorite journals. Each issue addresses one topic, in this case Nietzsche’s The Use and Abuse of History. It was almost as if in a planning session, the editors setting around their conference table had ironed out the question, “What topic can we do that most directly addresses the concerns of subscriber Cowan?” All of the articles are excellent, but the three that most resonate with me now are Kirsten Sanders’ The Evangelical Question in the History of American Religion, Brian Patrick Eha’s On Patrimony, and especially Elizabeth Lasch-Quinn’s Pastlessness.

Lasch-Quinn is the most talented acorn from the tree of Christopher Lasch, proving again the old proverb. She writes:

…the stuff of history is not outside us—and cannot be cordoned off from our day-to-day lives. We are surrounded by the creations of people we never knew; we live amid their expressions, their constructions, their communications. And the loss of every living person comes a loss of history, because each of us is history. We are a walking, living, breathing, unfolding history, inseparable from the history around us. History is not only external but internal.

And:

We have seen how so many today desire to live without history, even in times of relative peace. The Cult of the New ravages in manifold ways, reducing hard-won works to rubble. Creative destruction…has been the governing mantra for so long that it is hard to retrieve memories of an alternative. To live without traditions of moral grounding is to cut ourselves off not only from the past but from the future…we might liberate ourselves. But we would also obliterate reality in the process.

But we would be better off seeing history as a matter of urgent need. We should recognize the cultivation of a historical disposition that combines stewardship and moral inquiry as one of the our most pressing endeavors, after feeding, clothing, and sheltering ourselves, precisely because it is a necessity if we are to succeed in all of the endeavors of this life. In the best of times, history is a mad race to grasp what we can before the evidence crumbles. In the worst, it is a matter of cultural survival. In more ways than one, we find ourselves today in a historical emergency.

I share Lasch-Quinn’s alarm. The rapidity of our loss of understanding, what she calls "Pastlessness,” is almost breath-taking to behold. The Cult of the New rides forward victorious on nearly every front. So, this country I still love is, nevertheless, one that exasperates me. I have no shortage of ideas about just how we have arrived at our present juncture, as well as having some pretty settled notions about where it is all headed. And I do not think there is much we can do about it. Perhaps a different people could do so. Just not us. Things will chug along, until they don’t.

There’s no need to be gloomy about it, however. I agree with John Lukacs, who wrote: So living during the decline of the West—and being much aware of it—is not at all that hopeless and terrible. Indeed, what an exciting time to be alive today! But you have to turn much of the noise off to see this, I think. For example, I tend to avoid any headlines containing the words Arizona, Texas, Florida, Election, or Guns. It should be obvious; these are distractions that keep us from seeing the real story. Accordingly, I no longer worry that half of our citizenry have chosen to believe a fantasy. Over our history, incredibly, we’ve fallen for worse and larger ones. And who can tell what the other half believes, if anything.

These, of course, are mere symptoms, a reflection of the broad shallowness of what passes for American culture. It didn’t have to be this way, for we started from a strong foundation. But along the way, in pursuit of abstractions and avaricious aspirations, we have seemingly jettisoned many of our essential underpinnings. We find ourselves unmoored, adrift, and AWOP (alone with our phones.)

The fact that we have forgotten our very own stories speaks to the cultural poverty accompanying our Pastlessness. I am not just talking about our national myths, but the stories that families have told about themselves from time immemorial. These familial stories give context to our existence, and guide us in building lives of meaning and purpose. I find that most Americans today have little sense of where they fit into any narrative larger than themselves, or even worse, many do not even recognize that there is anything beyond satisfying their particular desires. My problem, on the other hand, is that I have too many stories.

And yet, I am hopefully, as was Lukacs. History and life consist of the coexistence of continuity and change. Nothing vanishes entirely. In this new age that is taking shape, the one to be inhabited by succeeding generations, I think they may well be in need of some of theses tales, that there may very well be a place for storytelling. And remembering.

***

The strands of my stories twine together, forming a thread of history that wraps around my own life. My task is to simply preserve them and to pass on to my family—not only my boys, but to my cousins who, against all odds, share in my love for this sort of thing. My sons are interested in the old tales, and they would, at least in theory, listen to me spin them. I have to admit, however, they would grow impatient with the “roundaboutedness” of my telling. This way they can read at their leisure, and hopefully the strands of the stories twine round their own lives.

I started asking my dad about these family myths almost sixty years ago, when I was eight. I remember it distinctly. Someone must’ve convinced my dad that now that he was “successful,” he needed to take a vacation. I cannot imagine it being my dad’s idea. And so, we found ourselves on a whirlwind road trip to Colorado in a new, 1963 two-tone Coupe de Ville. I have never romanticized or sentimentalized anything about my life; but if there was ever an idyllic, golden moment for me, it was this: just the three of us, my parents and I, alone together, away from their routines, away from all the cattle and their jobs and cares. As the blankness of the Texas Great Plains whizzed by, I remember leaning over the front seat peppering my dad with questions, mainly about history and our family. Once in Colorado, there would be other things to hold my attention.

In that context, he humored me, and this was the gist of the first tale: “There were three Cowan brothers who deserted from the Confederate Army and came to Texas.” That was it. But from that beginning, my interest in my family’s history began. Over the next twenty-two years, there would be countless other stories. As I eventually put it together, my dad’s synopsis was at least true-ish. The three brothers part was correct. But only the oldest was drafted into the Confederate Army against his will, deserted, and came to Texas. The next brother crossed over into Indian Territory and joined the Union Army. The third was too young to fight on either side. TWe never had the least bit of shame about the desertion; it was seen as an act of conscience, in which we took pride. This largely explains my disinterest in the military service of all my other ancestors of that generation, who more or less fell in with the folly that was the CSA.

The next major story in that family’s thread concerned the son of this deserter, my great-grandad William. He was an eight year old boy when they left for Texas, later telling stories of his falling into the Red River and shrinking his buckskin garment. The gist of this second story went something like this: As a young man, he fell in love with the daughter of a neighboring rancher. This family had the reputation of being a proud family, and the young suitor didn’t measure up in her father’s eyes. Instead, Mary was married-off, so to speak, to the son of another ranching family. In short order, the chosen husband deserted her and their child. But William remained constant in his love, working for her brothers for seven years until such time as her errant husband could be declared legally dead. They finally married and became the parents of my grandad and his two sisters. There is much more to the story, but it is not the one I am telling now. This story is an older one, concerning Mary’s eldest brother.

***

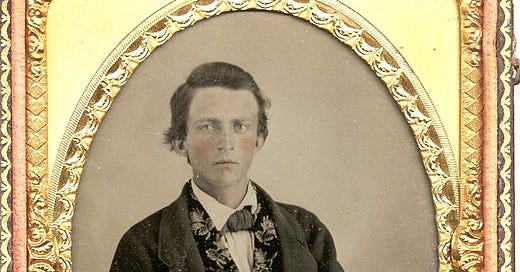

In a proper antique frame, in the hallway of our home, hangs the picture of a handsome young man sporting a colorful vest underneath a coat that is slightly too large for his frame. With his eyes cut slightly to the right, he nevertheless stares resolutely into the future. This young man was my Uncle Charles, and the photograph dates from 1862 when he was 17 years old. He would not live to see 21. Though only a copy, it has hung in our home for over 30 years. A cousin in the Dallas area possesses the original daguerreotype.

The occasion for the formal photograph was his having just been drafted into the Confederate army. Desperate for soldiers, the Conscription Act of April, 1862 cast a wide net across the South, netting anyone between the ages of 16 and 55. And so this 17-year old uncle, and his 44-year old father (my great-great grandfather) were both drafted. I do not know how strongly they favored secession, if at all. Many Texans did not. The extended family, all Tennesseans, had never been slave owners, and since 1853 had lived in a frontier region far removed from anyone’s imagined Old South. But still, they were loyal to Texas, and at that time Texas was Confederate.

Unlike many Texas recruits, Uncle Charles saw real action, of a sort, in Louisiana. A significant number, if not most Texas conscripts never left the state. In fact, many joined up to guard the frontier against the Comanches, specifically as an alternative to going East to fight their Northern brethren (the path chosen by another great-great grandfather in the same region.)

At war’s end, Uncle Charles returned to the ranch home near Comanche Creek in the Texas Hill Country, near the Llano and Blanco County line. His mother had died during the war, but his father and siblings were all there. At that time, his father’s two brothers lived in the area, as well. Several colorful stories of this era survive from these connections, but before long both had fanned out to other parts of the frontier. In fact, his Uncle Carey and Aunt Jane enlisted Charles’ help in their move to Mountain Home, down in Kerr County.

After performing this service to his family, Charles started back towards home in the empty buckboard. In was in July of 1865, so undoubtedly the heat was intense. He had to pass through the German settlement of Fredericksburg, and the reasons for stopping off there then were much the same as they are today: good German food and beer. Perhaps he lingered there longer than was wise.

About four miles north of Fredericksburg, Uncle Charles decided to stop and set up camp for the night beside a creek. He was still sixteen miles from home and he would push on the next morning. This proved to be his undoing. During the night, a band of Comanches found him, tied him to a wagon wheel and tortured him to death. His screams could be heard by the family in the nearest farmstead, located up the valley.

Word reached home, and before his father, brother-in-law and others left to retrieve the body, they dug a grave on the knoll above Comanche Creek. This plot was next to that of his mother, who had died the year before. Once the party reached the site of the murder in Gillespie County, however, they made the decision to bury the body there instead of transporting it in the July heat all the way back home. The open grave above Comanche Creek did not remain long open; a neighbor woman died and she was buried in the spot intended for Uncle Charles.

Uncle Charles’ murder was the harbinger of worse times to come. Federal troops had once helped protect the Texas frontier against Indian raids. Secession had wiped all of that off the table, and in the wake of a brutal four-year war, there was not yet an Army presence on the Texas frontier. The string of homesteads along Comanche and Sandy Creeks were dangerously exposed, being then on the fringe of settlement. The oldest sibling, my Aunt Ann, was already married, and according to family lore never stepped outside the house during this time without her six-shooter strapped to her hip. My great-great-grandad, a widower with six minor children to care for, moved two counties east for safety, leaving only the married daughter on the ranch. It would be thirteen years before they could return to their home on Comanche Creek.

Fifty-eight years later, in 1923, Uncle Charles’ younger brothers, Henry and Carey, along with their nephew (my granddad Henry), and perhaps some others, attempted to locate the 1865 burial site in Gillespie County. But the trail had grown cold. Undaunted, Uncle Henry’s granddaughter picked up the challenge again in the mid 1990s. With her take-charge personality, I believe Cousin Mada thought she could locate Uncle Charles’ grave by sheer force of will. She left no stone unturned, but it eventually became apparent that there was no surviving record of the burial location, either in print or in memory.

I really enjoyed working with her on the research, just as I had enjoyed my time a generation earlier with her aunts Pearl and Siambra; all three being personable, gracious, and keenly perceptive. Having an interest in history, or at least a desire to pass along the old stories, often puts you in contact with the most interesting relatives. The others, those who are too busy for this sort of thing, are usually the ones who first slip from historical memory anyway.

Although we could do nothing for Uncle Charles, Mada and I were able to mark the graves of his maternal grandmother in North Texas, and his great-grandfather, a veteran of both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 in Tennessee. And between the two of us, we also pinpointed the abandoned cemetery where two other siblings were buried during the family’s thirteen year sojourn further east.

***

In the Orthodox faith, we say “Memory Eternal.” This sentiment, however, has been with me all my life, I think. And so, I have sporadically marked the graves of various relatives whose burial places were in danger of being lost to memory. Even so, I still had a long list remaining. As the decades rolled by, I figured I had better find an affordable way to do this, or just to leave it undone. I was fortunate to find a monument company that would work with me: they would provide small inscribed footstone-sized stones for $25 apiece, if I ordered ten at a time. And so, during the summer of 2021, I placed fifteen markers: one in Oregon, one in Indiana, two in Georgia, two in Alabama, two in Mississippi and seven in Texas. I am probably one of the few people who has boarded a flight with a granite footstone and a zip-lock bag of Sakrete in their rolling luggage. This last summer I placed ten monuments, all in Texas.

As his actual burial site is lost to memory, I decided to place a stone for Uncle Charles in the family plot at Comanche Cemetery, where the family had originally intended him to be buried. There’s a nice family section, with a total of about seventeen relatives buried there. The cemetery contains one unknown grave, said to be the oldest burial there. I had always thought my great-great-grandmother’s, in 1864, was the oldest. Hers is at least the oldest marked grave. The closest available spot was to the south of his father’s second wife, whom he married after Uncle Charles’ death.

My closest relative buried at Comanche is my grandad’s older half-brother, the child of Mary’s ill-fated first marriage. But this remote cemetery has always been a touchstone for me, the physical link with that branch of my family (my grandad’s maternal line.) I have been visiting off and on for almost fifty years.

It is hard to image what this land was once like. Mind you, the Hill Country is still breathtakingly beautiful, but it is nothing like what the first pioneers saw. Nor is my own part of the state, for that matter. To read of those early accounts, much of Texas must have seemed like a giant park to these settlers: verdant grasslands, open forests of ancient trees, with little to no underbrush. In this respect, the Texas Hill Country must have been especially beautiful with scattered groves of live oaks shading its grasslands.

But civilization quickly took its toll. In this area of limited rainfall, the over-grazing of cattle helped to deplete the thin, rocky soil. In addition, cows basically do two things, and in that process they help spread the growth of mesquite, cedar and youpon. Without vigilance, the open meadows could quickly transition to scrub land, and from there into thickets. In my own lifetime, I remember driving across pastures to this cemetery forty-five years ago. The trail is still there, but the pastures are gone, replaced by mesquites. One can still catch glimpses here and there of what the land once was, for the natural beauty is still evident, just of a harsher nature.

And so, I stand at the cemetery and try to imagine what it was like back in that day. Without the mesquites and cedars, the broad hillock would have offered a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. You gets little sense of that today, as the site is becoming merely a clearing in the midst of thickening web of mesquite and underbrush.

Access to the cemetery used to be by way of a pasture road that wound through the pasture back to the creek crossing. I was never sure about whose property I was on, or how many properties I crossed, as there were no fences. All that is changed now. I made a pilgrimage several years ago and for the first time encountered a fence with a gate blocking my way on this well-established path. At that time, I simply parked my car there and walked the rest of the way.

Then in 2021, on my first attempt to set the stone, I came to the same place, but this time the gate had a No Trespassing sign prominently attached. While I know that there are prescriptive easements that attach to established cemetery accesses, I am also respectful of property rights, so I left and did not visit at that time. Once home, I researched the property ownership and discovered that the property had been purchased the previous year by a doctor in San Antonio. I reached out to him in the politest way possible, and soon received a letter from his lawyer, advising me that in no uncertain terms that there was no access across the property to the cemetery.

Well, I do know a thing or two about boundary law. I was a land surveyor for over thirty-five years, and I have taught a Boundary Law class at the university level for the last fifteen years. But, I played nice and continued the dialogue, casting my request in terms of an old man wanting to visit this family cemetery once more before he dies. And so after receiving permission, I found myself trudging across his land with a shovel in one hand, and a five-gallon bucket containing the stone, a bit of Sakrete and some water in the other. (I have since learned that there is a more direct access to the cemetery across the next property, though general access there is also restricted by the locked gate at the road.)

There is now a concreted culvert across Comanche Creek, as there are occasional burials here still. The most recent occurred two months following my visit. But the weird thing is there is actually two cemeteries, instead of one. I do not have the story on how this happened, but human nature being what it is, I can surmise.

My relatives are buried in the very oldest part, consisting of basically three extended families and their connections, totaling fifty some odd burials. But almost as old is the area just east of my family plot. This is the separate preserve of the two interconnected families who were the largest ranchers in the area. An old stone wall remains that originally set their graves apart, but they long ago outgrew that space. You might say that the stones in this east portion are more substantial than the graves in the western portion. And they are entirely of just two related families. Almost fifty years ago, my cousin Siambra alluded to some kind of squabble in the distant past. She never elaborated on exactly what happened.

I got the idea that the eastern burials thought themselves a little better than the rest. This is ironic, as it was my own family here that a reputation for pridefulness. But the end result is there are two separate and distinct cemeteries butted-up against each other. My family is in the Comanche Cemetery West, enclosed within a 4-ft. high chain link fence. The last burial in this section was my granddad’s first cousin in 1932. The more affluent eastern section—Comanche Cemetery East, I suppose—is enclosed, in case someone missed the distinction, by a 6-ft. high chain link fence.

There was not always such a sharp division between the families, however. From family lore, I know that in the late 1890s and early 1900s, my grandad and his sisters would return to the area during the summers and have picnics and get-togethers with other young people of their age, including those on both sides of the cemetery divide. We have one picture showing a gathering at the big house for this more affluent ranching family (picture above.) It looked like a rancher’s house from one of those 1950s movies which depicted a wealthy rancher warring against the virtuous small farmers or sheepherders. The house remains today, though barely recognizable.

One picture from that era shows my youngest great aunt, wearing an over-sized bonnet, sitting in a buggy with a friend, attended-to by a young man of the area. Maybe she had beaus there, for all I know. But she went to college instead, became a teacher, and married and lived her life out elsewhere.

To be completely accurate, there are actually three cemeteries on the hilltop. To the north of the western cemetery is another small chain link enclosure around a young live oak. Within the fence are the graves of two men, of no apparent connection to any of the families buried in either cemetery. They were probably ranch hands. One was Hispanic.

My Uncle Henry kept the ledger for the old cemetery. Over fifty years ago, the cemetery caretakers took that information and placed small granite markers on the unmarked graves, much like I am doing now. The markers were Texas pink granite from nearby Marble Falls, with only the name inscribed upon them. Such is the marker for my grandad’s half brother. The two graves in the small, separated plot are marked in exactly the same way, and obviously at the same time. And then a chain link fence was built around this small plot at apparently the same time the old cemetery fence was erected. These men were clearly “outsiders,” but even so, they were remembered and accorded the same respect as everyone else.

It was midday by the time I had finished my undertaking. For once, I had forgotten my hat, and so had my tee-shirt wrapped around my head. My car and water bottle were about a mile away, so I wisely decided to start back, perhaps for the last time from this spot. But as I hiked back, I had time to think about human relationships, and the story below the surface of these three carefully delineated, but adjacent graveyards. I can only conclude that the great levelers and equilizers of our time have their work cut out for them. Because unless human nature takes a turn, then Hierarchy will always find an expression.

You’d expect a lawyer to understand that the law provides for access. Texas Health and Safety Code Sec. 711.041 “Access to Cemetery” seems pretty clear.