I spent a wonderful afternoon last week with my oldest friend. We have been getting together weekly, often for lunch, for over thirty years. As I am of a certain age and he twenty years older than that, each of us are keenly aware of just how precious these small reunions can be at our stage of life. A week earlier we had driven out to his farm, where I helped him water the magnolia saplings he had planted here and there in the woods. They were not for show or display, no one would even know they were there without leaving the pasture and tromping into the forest. I was touched beyond words, watching him carefully pour water out of milk jugs around the young trees. Magnolias will take twenty to thirty years to mature, so he is planting for the world that comes after him. This is stewardship as it should be; tenderly nurturing rather than exploiting, leaving the world better than you found it. Such is all too rare these days. Efforts like this, I think, express our innate desire to recreate a Paradise lost, always inadequate and transitory, but nonetheless necessary for true human flourishing.

This time, however, we just sipped coffee in his study and talked. As is often the case, these sessions are heavy with his reminiscences of a long life well-lived; of which I never tire of hearing. But like any skilled conversationalist, my friend is self-aware lest he monopolize the conversation in any way, always seeking to bring it back to my perspective or agenda. I hope I have learned something from over thirty years of this. I may be bursting with things to say, but the better approach is always to ask the other person about themselves.

Beyond reminiscences, our talk effortlessly bounces from family to history to past travels to literature to current events to theology and back again to history. And these days, talking about contemporary politics is almost as rare for us as talking about sports, which is to say, non-existent. So somehow, the subject of the Civil War came up, as it often does when two Southerners sit down to talk. We both have impeccable Southern credentials—me perhaps more so than him—and we call the struggle what it was, a “civil war,” rather than engage in the sectional silliness of “War Between the States,” or God forbid, “War of Northern Aggression.”

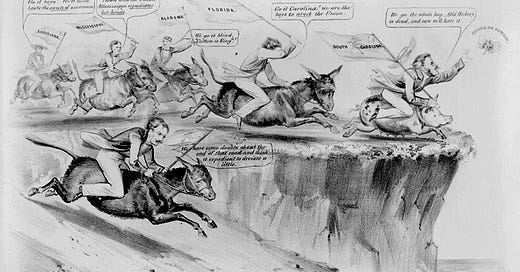

He was making the point of the utter stupidity of Southern secession. Blinded by ideology, both ill-informed and uninformed, Southern firebrands foolishly marched their region off a cliff, taking over 600,000 lives with them. And it is clear that their secession was intentional rather than reactive, at least in the Deep South. What little they knew of Abraham Lincoln, they knew wrong. A consistent moral opponent of slavery, he had, however, never been an abolitionist. His political position was to always oppose, either legally or constitutionally, its spread beyond where it was already established. Such nuances were lost, however, in the fanatical caricatures of Southern propogandists.

And then there was the fiasco of the Democratic conventions of 1860 (three, in total). Southerners insisted on a “Dred Scott” position on slavery, where it was protected everywhere in the territories, and by extension, everywhere else as well. The expected nominee, Stephen A. Douglas, the foremost proponent of popular sovereignty (letting the territories themselves decide—a “states rights” position if there ever was one,) could not run on that position, much less hope to pick up any states outside of the Deep South. The result was foreordained, two Democratic parties and assured defeat. In truth, Lincoln would have probably won the electoral vote anyway, but not for the intransigence of the South, the Democrats in 1861 would have been in a far stronger position to oppose a weakened President Lincoln elected with a minority of the popular vote. But neither electoral strategy, nor even congressional gamesmanship was ever the end game; that was always secession itself.

My friend made the point that if the South had not seceded, their Democratic presence in Congress—not to mention having the Taney Court in their back pocket—could have stymied any initiatives put forward by the Lincoln administration. Divided government is not a new thing. They could have made good on their stated goal of protecting the institution of slavery, making the eventual abolishment of same something for the far distant future. Today, the very idea that in 1860, a modern western Slave Society could have been maintained and projected into the future, even the 20th century only forty years ahead, strikes me as patently absurd. And of course it was—a measure of the magnitude of the cherished delusion that the South both nurtured and fed upon.

In speaking of the antebellum South, my friend chose his words carefully and deliberately, saying, They believed in an alternative narrative; one that was…not…true. I totally agreed, and cautiously (in light of our avoidance of contemporary politics) compared such illusions grown in the hothouse of epistemic bubbles to the current belief in the “Big Lie.” He gently—and correctly—reminded me that such thinking was not the sole preserve of the Right, as the Left is more than capable of the same itself. I have come to the conclusion that for any thinking person to ascribe to the delusions of either is a non-starter. What we are left with is a choice between the increasingly attractive option of opting-out of the entire debate/process, or holding one’s nose and choosing the least destructive delusion on offer.

This caused me to think a bit about the nature of our respective Grand Delusions. The Right denies the reality of events, clueless to its eventual Emperor Has No Clothes moment. The Left, however, seeks to deny the very nature of humanity itself. Both worship at the same altar, but their beliefs are predicated upon differing hermeneutical approaches within the Cult of Progress. The former believes the fantasy of a technological harnessing of apparently limitless resources to produce an ever-expanding material prosperity, all without consequential damage to the society at large. The Left believes in the fantasy of a technological harnessing of the apparently limitless ability to refashion mankind itself, regardless of the demolition of existing societal structures, and again, all without serious consequences. This latter one, while indeed the more extreme, worries me the least, as it is the more difficult case to make—indeed, often farcical in its extremities—and seems likely to eventually collapse in upon itself. The former, however, I consider the more dangerous at this moment in history, as they appear fully ready and prepared to project and maintain their Will to Power. At these times, you cannot go wrong by referencing Shakespeare, “a plague of both your houses.”

***

That brings me to back to the old South again, by way of Henry James. “How?”, you might ask? James falls in the category of Notable Writers I Have Not Read, and more specifically in a subcategory of that entitled And I Do Not Intend to Read. He came from a moneyed New York family, traveling extensively in Europe during his youth. By the time he was twenty-six James had settled permanently in Europe, and in England from age thirty-two, becoming a chronicler of both the Gilded Age and the Edwardian Era—on both sides of the Atlantic. He is no doubt, a Great Writer, but I made the transition from Dickens, Trollope and Eliot on end, to the great works of the 1920s by way of Forster and a bit of Wharton, without recourse to James. Having read Howard’s End, A Room with a View, The House of Mirth, and The Age of Innocence, I feel no compelling reason to open James (though my new interest in “ghost stories” may lead me to The Turn of the Screw.)

Recently, however, I read an article in the London Review of Books, entitled “Visions of Waste,” a review of James’ 1906 The American Scene. In 1904 James returned to the U.S. for a lengthy visit and speaking tour. His travels took him from Boston to Florida to the Pacific coast and many points in between. This sounded interesting to me, and it turns out that I had the book in my Library of America collection. I started with them at their beginning, and remained enthusiastic about the project for a number of years. But with the limited scope of only classic American authors, you eventually reach the point where it should stop. I began to lose interest when they dropped to B-list tomes, and cancelled my subscription when it seemed they were headed even lower.

I was interested to read his perspective on the U.S. after nearly thirty years absence from the homeland which had never truly been his home. The American Scene is loosely chronological, but more accurately topical by location, allowing the reader to dip and out to read the sections that interest him. Reading James can be infuriating, but worth the effort. I love richly detailed prose, and dislike Hemingway-ish sparseness. James, however, strings together endless compound phrases connected by far too many qualifiers, to form, at first reading, an incomprehensible sentence. I found myself mental diagraming as I read to figure out the point he was actually trying to make. In truth, my first impulse was “why bother?,” but after getting to the heart of the matter, the jewel of his thought was there, shining like a diamond.

I was curious what he had to say about the South. James does not approach the region with the prejudicial condescension too often once employed by Northern visitors, to the consternation of Southerners. And I count myself among that number; criticism is just fine (and usually justified), condescension altogether a different thing. And that is what makes James such an excellent observer, for he had a keen analytical mind, approaching the nation, and its regions, as a curious European trying to make sense of it all, all accomplished without using the lens of regional loyalties. Though less well known, perhaps this work should be linked in thought to that of de Tocqueville. They are both viewing the country from much the same perspective, separated by seventy-five years.

Indeed, James admits to being predisposed to like the South, that is the “Old South” of romance. Of that, he finds very little of substance. James noted that “I was to recognize how much I had staked on my theory of the latent poetry of the South.” He traveled from Washington DC to Richmond, then through the Carolinas to Charleston, and then on to Florida—all by train. Washington was no longer a Southern town, but he experienced his first intimations of it there. Richmond he found sad and disappointing. James thought the Carolinas blighted. Charleston offered hints of what he had been straining to see, but little more than a glimpse here and there. James found Florida over-hyped even then. Of the region as a whole, he observes:

It’s a bad country to be stupid in—none on the whole so bad. If one doesn’t know how to look and to see, one should keep out of it altogether. But if one does, if one can see straight, one takes in the whole piece at a series of points that are after all comparatively few.

James found Richmond a strange city, indeed not at all “Southern.” I recall thinking much the same from my visits there in the 1990s—a nice enough city, to be sure, but now really a Southern one. He spoke of the “tragic ghost-haunted city…centre of the vast blood-drenched circle,” having “no discernible consciousness…of anything,” rather being “bland and void,” devoid of the “Southern character,” evidencing instead “a large sad poorness.” Any Northern city of similar size, James noted, “would, however stricken, have succeeded, by some northern art in pretending to resources.”

While in Richmond, he visited the temple of the Faith—the White House of the Confederacy and the Museum of the Confederacy; as well as the Capitol, St. Peter’s church where Jefferson Davis received the news of Lee’s surrender, the Public Library, and Lee’s equestrian statue (of recent removal). Considered as a whole, it found it small and underwhelming, lacking in vision, for such a momentous role it played in history

.

Of the Museum, he wrote of the “very nudity and crudity…the pathetic poverty of the exhibition.” Indeed, he found the place “weak—adorably weak.” And James’ commentary on the struggle it commemorated put me in mind of the discussion my friend and I had only days earlier.

Tragically, indescribably sanctified, these documentary chambers that contained, so far as I remember, not a single object of beauty, scarce one in fact that was not altogether ugly…that spoke only of the absence of means and of taste, of communication and resource….here was a pale page into which he might read what he liked….the heritage of woe and of glory…

And:

…the sorry objects..so low the aesthetic level, it was impossible , from room to room, to imagine a community, of equal size, more disinherited of art or of letters…the illiteracy seemed to hover like a queer smell; the social revolution had begotten neither song nor story…

I was tasting mystically, of the very essence of the old Southern idea—the hugest fallacy, as it hovered there to one’s backward, one’s ranging vision, for which hundreds of thousands of men ever laid down their lives. I was tasting of the very bitterness of the immense, grotesque, defeated project—the project, extravagant, fantastic, and today pathetic in its folly, of a vast Slave State (as the old term ran) artfully, savingly isolated in the world that was to contain it and trade with it….that the absurdity had once flourished there; and nothing, immediately, could have been more interesting that the lesson that such may remain, for long years, the tell-tale face of things where such absurdities have flourished.

What was the sadness, taken all round, but the incurable after-taste of the original vanity and fatuity, with the memories and penalties of which the very air seemed still charged….The Southern mind of the mid-century in the very convulsions of its perversity—the conception that, almost comic in itself, was yet so tragically to fail to work, that of a world rearranged, a State solidly and comfortably seated and tucked-in, in the interest of slave-produced Cotton….Since nothing in the Slave-scheme could be said to conform—conform, that is, to the reality of things—it was the plan of Christendom and the wisdom of the ages that would have to be altered. History, the history of everything, would be rewritten…this meant a a general and a permanent quarantine; meant the eternal bowdlerization of books and journals; meant in find all literature and all art on an expurgator index. It meant, still further, an active and ardent propaganda; the reorganization of the school, the college, the university, in the interest of the new criticism.

James found the whole Confederate project a great folly, one that was “queer and quaint and benighted.” One point I have never considered, one that James observed, was the impossible self-imposed quarantine the South would have needed to maintain between its cloistered society and the rest of the world. With an eye for the aesthetic, James described the relics on display, indeed the entire idea, as “artlessly perverse…untouched by any intellectual tradition of beauty or wit.” “For him, “so barren a polity, the idea of the perpetual Southern quarantine” represented the very “trivialization of history” and its “inaccessibility to legend.”

…no leaders of a great movement, a movement acclaimed by a whole nation and paid for with every sacrifice, ever took such pains, alas, to make themselves not interesting. It was positively as if legend would have nothing to say to them; as if, on the spot there, I had seen it turn its back on them and walk out of the place…if the question is of legend we dig for it in the deposit of history, but the deposit must be thick to have given it a cover and let it accumulate.

His comments on American public libraries, and not just the one he visited in Richmond, was that they could be compared to the “mast-heads on which spent birds sometimes alight in the expanses of ocean.”

The Lee statue (recently removed to the Black History Center and Cultural Museum of Virginia) did not inspire James either. He faulted the monument not so much for the sculpture, but rather for the pedestrian setting in a non-descript residential area, “somehow empty in spite of being ugly, and yet expressive in spite of being empty.” To James, the “desolate” statue helped explain the “historic poverty of Richmond,” which is “the condition of having worshipped false gods.” (emphasis mine.)

Lee’s stranded, bereft image, which time and fortune have so cheated of half the significance, and so, I think, of half the dignity, of great memorials, I recognized something more than the melancholy of a lost cause. The whole infelicity speaks of a cause that could never have been gained.

James notes the obsession of many Southerners of that day to inordinately dwell upon the conflict.

The collapse of the old order, the humiliation of defeat, the bereavement and bankruptcy involved, represented, with its obscure miseries and tragedies, the social revolution the most unrecorded and undepicted, in proportion to its magnitude, that ever was; so that this reversion of the starved spirit to the things of the heroic age, the four epic years, is a definite soothing salve—a sentiment which has, moreover, in the South, to cultivate, itself, intellectually, from season to season, the field over which it ranges, and to sow with its own hands such crops as it may harvest…

At the Museum of the Confederacy, James struck up a conversation with an amiable young Virginia farmer who had come to the temple to venerate the icons. He good-naturedly assured the author that he stood ready to do it all again if called upon to do so, for, as he said, “That’s the kind of Southerner I am!” James wryly observed that his “consciousness would have been poor and unfurnished without this cool platonic passion. With what other pattern…could he have adorned its bare walls? The amiable and engaging Virginian assured James that he would not hurt a “Northern fly.” The author, upon reflection, and remembering the subjects of their extended talk, thought that “though he wouldn’t have hurt a Northern fly, there were things…that…he would have done to a Southern negro.”

James’ gave vent to his deprecation of American churches, not just Southern ones, while in Richmond:

…one of those decent and dumb American churches which are so strangely possessed of the secret of minimizing, to the casual eye, the general pretension of churches…they are reduced to the inveterate bourgeois level (that of private, accommodated pretensions merely)….they remind one everywhere of organisms trying to breathe in the void, or of those creatures of the deep sea who change colour and shrink, as one has heard, when astray in fresh water…

He remembered that grand buildings both existing and planned in Washington, full of “confidence and energy,” but noting “what it is you so oddly miss.”

Numberless things are represented…but something is absent more even than these masses are present—till it at last occurs to you that the existence of a religious faith on the part of the people is not even remotely suggested… you liken it perhaps…to a picture, nominally finished, say, where the canvas shows, in the very middle, with all originality, a fine blank space….”

The field of American life is as bare of the Church as a billiard-table of a centre-piece; a truth that the myriad little structures “attended” on Sundays and on the “off” evenings of their “sociables” proclaim as with the audible sound of the roaring of a million mice…the difference between the deep sea of the older sphere of spiritual passion and the shallow tide in which the inhabiting particles float perforce near the surface…the consequent permeation will be of values of a new order. Of what order we must wait to see.

Of Charleston, James was more kindly disposed; but before that he had to pass through the Carolinas. He admitted that “it was a monstrous thing…to sit there in a cushioned and kitchened Pullman and deny to so many groups of one’s fellow-creatures any claim to a ‘personality,’” allowing him “his awful modern privilege of this detached yet concentrated stare at the misery of subject populations.” He found the country between the two cities to be grim and dreary, leaving him with the distinct impression that “nobody cared—cared really for it or for anything.” This is unfair, perhaps, but he attributed it to a hard inexorable fate where many things were “ruled out.”

He found in Charleston a bit more of what he was looking for, with closed gardens of “the ancient sallow crones who guard the locked portals and the fallen pride of provincial palazzini.” James found in these real gardens behind walls, unlike those in the North, “exactly what one would have wished…some final sleep, of the idea of success…where resignation might sit in the shade…as some dim dream that things were still as they had been—still pleasant behind garden walls—before the great folly?”

To James, this was a “city of gardens…superficially prim…[with] the suggestion of a social shrinkage and an economic blight, irreparable.” Here in Charleston, but certainly not in Richmond, he nevertheless detected “the ghost of a rococo tradition, the tradition of the transatlantic south” where “memory of other lands, glimmered generally in the decoration.” James was most at home in the graveyard under the south wall of St. Michael’s Church, “the sweetest corner of Charleston.” My own memories of Charleston are now less distinct, but this spot I remember as well.

James’ recollections of Florida consisted of San Augustine and Palm Beach and the railroad track connecting them. Of the former, he concluded that the city was basically a hotel, The Ponce de Leon, a Spanish renaissance style palace on the European order. He summarized the city’s portrayal of its own history by saying “that when you haven’t what you like you must perforce lie, and above all misrepresent, what you have.” One commentary on Florida in general is to my liking.

Florida, ever so amiably, is weak. You may live there serenely, no doubt—as in a void furnished at the most with velvet air; you may in fact live there with an idea, if you are content that your idea shall consist of grapefruit and oranges….but press upon the board with any greater weight and it quite gives way—its three or four props treacherously forsake it.

At one point, James comments of the totality of Confederate memorializing in the South of 1904.

How…can everything so have gone?—assuming indeed that, under this aegis, very much ever had come. How can everything so have gone that the only “Southern” book of any distinction published for many a year is “The Souls of Black Folk,” by that most accomplished of members of the negro race, Mr. W. E. B. Du Bois? [This, of course, long before the Southern literary renaissance beginning in the 1920s.] Had the only focus of life then been Slavery? …so that with the extinction of that interest none other of any sort was left. To say “yes” seems the only way to account for the degree of the vacancy…

He has a point, I think. As a Traditionalist, my inclination is to always hang on to what went before, so to speak. But what is intended is the hanging on of the Good. James’ scope of interaction with the South is somewhat limited, at least in terms of direct contact, with members of his social class. There are, in fact, many Souths, and most of them never overlapped with Pullman cars, the closed gardens of Charleston, or the set at the Ponce de Leon Hotel. In spite of that, I feel his analysis has more than stood the test of time.

At times I also found myself deconstructing James' sentences in order to ferret out his intended observations. It was a small comfort, however, to know that you also had to it as well, Terry.