The Rightness of Ralph Adams Cram

Some thoughts

Ralph Adams Cram in Context

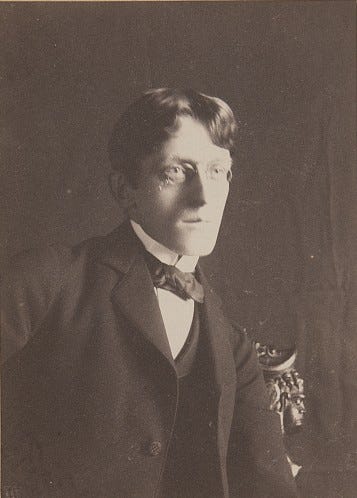

One pleasure of living with books is the discovery of neglected writers whose voices ring with clarity down through the ages. Ralph Adams Cram (1863-1942) is just that sort of author for me. His scholary dissertations on history form one third of triumvirate of wisdom for me: the others being Welsh author Arthur Machen (1863-1947), who could summon up the transcendent and the strange, and his younger compatriot, Edwin Greenwood (1895-1939), a master of broad humor. All three of these men were kindred spirits, and I would like to think that the two English friends were familiar with Cram’s work, and visa versa. For them, Modernity, erected on a foundation of industrialism, consumerism, and materialism, was a complete sham, full of hypocritical pretense and hollow rhetoric about progress, democracy and the Rights of Man. They also had a good idea of what was coming and why.

A New Englander, Cram was no Boston Brahmin, but hailed from New Hampshire, with deep ties to two small ancestral villages. The son of a Unitarian minister (the “Ralph” in his name was in honor of Ralph Waldo Emerson), Cram became a High Church Anglican after a conversion experience in Rome in 1887. He was a true Anglo-Catholic, accepting papal supremacy, and being as close to Catholicism as one could be and remain Episcopalian. Surprising to me, his birthday (December 13th) is a feast day in the Episcopal Church, which they observe here and there. I did not think they went in for that sort of thing. Cram ascribed to the Branch Theory, which viewed Anglicans, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox as the three branches of the Church.

Along with the Frank Lloyd Wright, Cram was probably the most noted American architect in the first half of the twentieth century. He championed the Gothic Revival style, mainly in ecclesiastical and collegiate settings. The Princeton campus is his creation, as is the unfinished Church of St. John the Divine in New York City, the Mellon family’s Liberty Presbyterian Church in Pittsburg, Calvary Episcopal Church in Americus, GA, and All Saints Chapel at Sewanee where my oldest son graduated in 2005. A bit closer to home is his design for the Rice University campus, including Lovett Hall, and the Central Plant, disguised behind an Italianate loggia and a campanile which hides the smokestack. His small All Saints Church in Peterborough, NH is said by some to be the most beautiful church in America. Indeed, some architectural historians argue that he should be much better known today, suggesting that his eclipse by Frank Lloyd Wright was undeserved. The building I would most like to visit, however, is not one of his grand Gothic churches, but rather the modest family chapel the Crams and some workers constructed on the back side of his farm in Sudbury, MA, the Chapel of St. Elizabeth of Hungary. In his words:

The guiding idea was to think and work as would pious peasants who knew nothing about architecture except that a church has round topped windows and that the altar end was finished in the form of a semi- circle......Reliance was placed on form and proportion to the almost total exclusion of ornament.....the stone and brick have been blended into each other in a more or less casual yet rather carefully studied manner, after the fashion that is to be found in the Italian and Spanish buildings of the earlier Middle Ages."

As much as I appreciate his commitment to traditional architecture, it is Cram’s writing that have resonated with me. My first exposure was a small 1893 work in the style of the Decadent Movement. From there, I moved on to his strange tales—”ghost stories,” if you will. Only then did I take on his essays, many published in small volumes. In the years 1917-1919, Cram published four short works which serve as a compendium of his world view, to-wit:

The Nemesis of Mediocrity (1917)

The Great Thousand Years (1918)

The Sins of the Fathers (1918)

Walled Towns (1919)

The Nemesis of Mediocrity or the Menace of Democracy

In The Nemesis of Mediocrity, Cram leaves no room for triumphalism in the war-torn West of 1917. As he put it, “inch by inch the valleys are being filled and the mountains brought low.” I do not think he would be much surprised by how it has spun out in the subsequent 108 years. President Wilson’s slogan from that era—“the world must be made safe for democracy”—was all the buzz at that time. Cram was not impressed, stating that although a noble sentiment, it would be meaningless without its corollary: democracy must be made safe for the world. Indeed, he concluded that democracy in 1917 had degenerated to the point that it was no longer “a blessing but a menace.”

I find this characterization prescient in light of the kind of democracy promoted in the dying West of today. The U.S. today resembles a Kandinsky two-sided painting: Chaos, control. Chaos, control. You like? You like?1 We may be forgiven for thinking that we have taken a step back from the abyss. I’m afraid we’ve only stepped away from the lip of the ledge, halfway down the abyss. Whatever this is, it is difficult to characterize it as “democracy.” Of course, it would have been even harder to so label the previous regime.

In Europe and Great Britain the situation is, unfortunately, even worse, much worse. Democracy applies only to the bien pensants. Those beyond the Pale will be charged with something (it doesn’t matter what). Perhaps an election will be cancelled. Unacceptable candidates are simply ruled ineligible to run. Legitimate elections that go the “wrong” way will not be recognized and subjected to professional protestation. All the while, this western tip of the Eurasian continent continues to believe that their actions are of profound importance to the rest of the world. The rest of Eurasia, Africa, South America, and increasingly in North America, shake their heads in disbelief. But no matter, the feckless Starmer plays war games with his imaginary soldiers. The Prime Minister of Denmark almost says Orwell’s “War is Peace” (close enough to count). The dominatrix Queen of Europe encourages her subjects to stock up on 72 hours of essentials to be ready for the coming invasion from Russia. If this is “democracy,” then Cram had it tagged exactly right as a “menace.”

Most readers will be surprised to learn that Cram believed that the greatest flowering of the ideal of Democracy occurred in the High Middle Ages. He saw Absolutism not as a mediaeval feature, but as a product of the Machiavellian Renaissance. This early concept of democracy viewed ethics and morality as the purpose behind any political organization; directed towards the establishment of righteousness and justice, The rise of Absolutism out of the Renaissance was followed by the “shattering of the sense of right and wrong by Calvinism and other Protestant phenomena, partly because their birth coincided with an industrial development that blotted out…all considerations except those of material benefit and of selfish advancement.” This disappearance of religion as a “vital force” was a major factor in “fixing the manacles of capitalism and industrial slavery on the world.”

Cram’s abhorrence of Calvinism is an important constant in his writings. As a New Englander, that was his patrimony, perhaps suggesting why his repudiation was so heated. I recognize the inclination, as I have had to temper my criticism of the fundamentalist sect that I came out of. But no matter, Cram returns to Calvinism again and again in his writings, unrelenting in his disparagement of same, seeing it as a pernicious and malignant blight on the psyche of the European.

Cram often refers to the three curses of the Modern Age—his Three R’s—as it were: Renaissance, Reformation and Revolution. He said that the first destroyed the claim of the Church, and the second and third destroyed the fact of the Church. And from this, “the thing we have so earnestly and arduously built up of Renaissance, Reformation and Revolution, with industrialism and scientific determinism as the structural material, is not a civilization at all.” Indeed, he concluded that it must be destroyed so that the ground can be cleared for something better. This is a radical thought, coming from a Boston architect of 1917, having some similarities with the contemporary concept of anarcho capitalism.

Cram concluded that often patriotism can “serve only as a costume easily laid aside.” Underneath he found “just the same old politician, learning nothing, forgetting nothing.” Finally, he noted that “nothing is added to the issue by rotund phrases about warfare for universal democracy.”

The Great Thousand Years & the Ruin of Renaissance, Reformation and Revolution.

My edition of this book was published in January 1918, after the Russian Revolution and before the defeat of Germany. But the original work had been published in 1908. The latter volume is twice as long, containing a second section entitled “Ten Years After.” But whether it was 1908 or 1918, it long predated Oswald Spengler’s 1926 Decline of the West. One wonders if Spengler had read Cram, for there are definite similarities in their views, even given the disparity in the respective lengths of their works.

Cram saw history as moving in rough 500-year epochs, and he made a plausible case for this, extending all the way back to ancient Egypt. He refers to the transition points between epochs as “nodes of history.” They are not hard and fast. Precursors to the coming age may long precede its demise (and Cram believed his era to be in that stage.) And reactionary explosions of the dying age may slop over into the succeeding age that has not yet defined itself. I believe we are in this latter stage now, with all the saber-rattling and posturing on both sides of the Atlantic. Indeed, he noted this phenomena, below:

...what often happens is that the great flowering is after the trunk itself is dead and decaying, but the men who make epochs and mar them, whether they are Benedicts, Ottos and Hildegrands, or Alarics, Calvins and Borgias, appear like clustered starts, beneficent or baleful, around that mysterious point that forms a node of history.

The Middle Ages, Cram’s “great epoch,” through the “the dizzy upward leap of Mediaevalism, reaching in a century the loftiest levels of attainment, continuing thereon for nearly three hundred years, then gently declining in a long glissade to the year 1453, with the rising line of the new era crossing it in its pathetic fall." I find it interesting that the Fall of Constantinople was a precursor to the Modern Age. Cram’s angle, however, is that the fleeing Byzantine scholastics from Constantinople tainted the Italian Renaissance.

He has harsh words for the founders of Modernity; “those whose destiny it was to bring the great epoch to an end in ignorance, anarchy and apostasy: Luther, Macchiavelli, Cranmer, Crumwell, Henry VIII, and the spawn of the house of Borgia."2 He concludes that the “worship of intellect, worship of force, worship of the ego” destroyed mystery and spiritual perception, leading to the end of sacramentalism, the abolition of conscience, and “the ancient instinct towards honour and chivalry,” and “individuality through communal unity.” The great synthesis of these forces ultimately saw “the unity of religion destroyed, the unity of philosophy destroyed, the unity of society destroyed, the disintegrating forces--relationalism, materialism, individualism..."

The age quickly devolved into an “unearthly farrago of Calvinism, materialism, anarchy, intellectualism and infidelity,” where “Great in the eyes of men were their works.” He noted, however, that “the astounding fabric of modernism still lacks by some courses its final capstone.”

I have believed this for a long time now, and I suppose I was just waiting for a man who wrote 107 years ago to give it a name. If you are a disciple of Progress, then these days must be scary times indeed. Something has clearly gone off-script. But if you believe that Progress is a hollow heresy, then accepting that we may, in fact, be living through the next “node of history,” is, well, pretty heady stuff indeed. I can’t think of a more exciting time to be alive.

But, Cram knew it was coming, but not quite there in 1918, but that the Renaissance epoch was dying with the “decadent violence of anarchy, profligacy and apostasy.” And he concluded that it would be the “hammers of God” that destroyed “the towering fabric of modernism.”

The Sins of the Fathers and The Three Errors of Modernism

Cram takes up his pen again, later in 1918, expanding upon previous themes. He saw the Great War as an inevitability, in a grand passage:

It was conceived in the very beginnings of modernism when first the Renaissance began to supersede Mediaevalism; it grew and strengthened as the Reformation entered its final form; it quickened and stirred as the revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shook the foundations of law and order in all Europe; it struggled for birth as industrial civilization waxed fat and gross in its century of blind evolution. Medici, Borgia and Machiavelli, Huss and Luther and Calvin, Cromwell and Rousseau and Marat; the regraters and monopolists of the seventeenth century, the corporations and exploiters of the eighteenth, the iron-masters and coal barons, the traders and the usurers of the nineteenth, the triumphant, Imperial Great Powers of industrialism in the twentieth century, prepared all things for its nativity, and when, on the first of August, 1914, a group of 'supermen' in Berlin acted as surgeons and midwife, it came to its birth, after long gestation, a thing neither to be denied nor escaped, an inevitable event born 'that the prophecy might be fulfilled.'

Cram expands upon his “Three R’s”, the forces which created the Modern Age.

The Renaissance exalted the intellectual standard, one that would be “sufficient in itself for the measuring and determining of all things.” Of course, the corollary to this would be the “abandonment of a super-material standard of right and wrong, with the consequent break-down of morals.”

The Reformation preached a denial of sacramentalism. This had the effect of paralyzing religion as a spiritual and ethical force.

Revolution—politically and socially—was the inevitable outcome of the Renaissance and Reformation, with “absolutism and tyranny, with force as the one recognized arbiter of action.” The “tyranny of crown and caste were overthrown, but the New Order could “substitute nothing but another tyranny in its place.”

Green and covetousness prevailed, “exalted above all virtues, and offered fabulous reward through surplus manufacture, the exploitation of labour, artificially developed trade-and usury-it was sufficiently convincing in its magnificent potency to win universal acceptance as the highest achievement of man in all recorded history.”

Cram then identifies three errors of Modernism:

Imperialism is the very antithesis of Democracy. Cram differentiates between the Ideal of Democracy, and the Method of Democracy as it was practiced in the West, “a very perfect blind for the triumphant imperialism that everywhere had taken its place." He characterizes the real democracy of Jefferson as something that “long ago became merely a collection of literary remains, an archaeological abstraction.” If we were honest with ourselves, we would admit to the truth of that. Imperialism always works downward from an authoritative source, while democracy’s essences are “differentiation, local autonomy, and a building up of authority from primary units." In the end, "Imperialism will always be its own executioner”. Cram concludes that Imperialism forgets that “the social unit is not the individual, as is claimed by the political, economic and social anarchists of the present day; it is not the State, that amorphous but annihilating fiction proclaimed by Teutonism”, but rather “it is the family, the primitive social group of father, mother and children, adding at either end, and temporarily, grandparents and grandchildren."

Another characteristic of Modernity is the loss of the qualitative standard, and its replacement by the Quantitative Standard; the change for the pursuit of perfection to that of the pursuit of power. Cram first detects this in the “Exile in Avignon” in 1305, then overtly following the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. This does not contradict his theory expounded in The Great Thousand Years, for the harbingers of change can long precede the actual beginning of an epoch, just as the reactionary events (as in today) can exceed its passing. In this pursuit of power, “the tendency of the whole world had been steadily in one direction.” And today, those clinging to Modernity know not how to consider the world otherwise. “In every case a sharp, deep line has been cut between all the rich, creative societies of the past, and modernism. History goes no further back than Jefferson, Pitt and Napoleon, thought ceases at the age of Adam Smith, Kant and Rousseau."

The third pillar of Modernism is so obvious it hardly needs stating. Materialism—the “ardur of getting, retaining and increasing” is the “driving spirit of modernism,” and ultimately its nemesis. Cram concluded that once you take out of the equation modern conceptions of comfort, physical luxury and our “pampered habits of material convenience,” one must agree that whether in Athens, Rome, Constantinople, or the Middle Ages of the Early Renaissance, that “civilization was expressed in higher terms than those we have devised for ourselves, in that man lived then in that environment of natural beauty prodigally provided for him, enhanced at every point by his own genius, and supplemented by ideals, aspirations, customs--illusions, if you like, that gave life coherency and a quality of joy and exultation unknown during the epoch of materialism.”

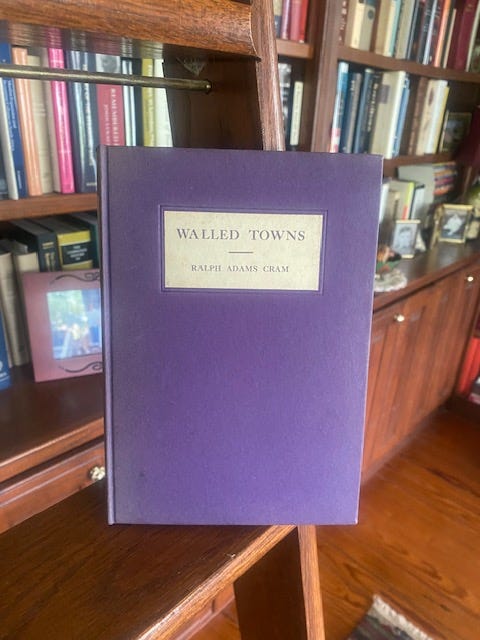

Walled Towns and a Third Way

Cram wrote Walled Towns in September, 1919. The war had been won, but the shape of the world to be was still in flux. Not content with cataloging the destruction, Cram actually charts a way forward, or as he puts it, a “way out.” He was not short of ideas on exactly what should be done with Europe. In late 1918 he published A Plan for the Settlement of Middle Europe: Partition without Annexation. He prepared a fascinating map, far more informed than the one President Wilson sketched on a map of Europe unrolled upon a floor in the Palace of Versailles. Cram’s was not a hard and fast proposal, the accompanying essay allowed for plebiscites and adjustments as needed. I found it breath-taking in its groundedness to the actual history of Europe, as opposed to the ideology of Wilson and the avariciousness of the British and French.

Cram returned “Germany” to its history. The German Empire dated to only 1870, a relatively new construct, one that he did not feel needed to be perpetuated. France retrieved Alsace and Lorraine, but between that and the Rhine was the Palatine, neither French nor German. East of the Rhine lay Hanover, Bavaria, and Saxony, with the Prussians (and the Hohenzollerns) consigned to East Prussia.

A healthy, defendable Bohemia was carved out of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. Poland has a Baltic port and a more realistic configuration than anything that actually transpired in 1919, 1939, or 1945–and certainly more historically intelligent that the current configuration of western Ukraine. Austria and Hungary were separated, but treated lightly; Austria kept Trieste, and Hungary retained Transylvania.

Bulgaria was given back its Ageaean coastline, and Roumania retained Bessarabia (Moldova). The most interesting bit lay on the edge of the map. Cram revealed a re-created Byzantium, with Constantinope and Smyrna remaining Greek and Christian, but not part of Greece. Turkey would, I assume, reconstitute itself in the Anatolian heartland without Constantinople. The fate of Trebizond lies beyond the scope of his map. Cram’s construction would make a great starting point for a game of What If Revisionist History.

Cram begins Walled Towns with a description of a walled city in western Europe where “there is no smoke and no noxious gas…no sounds but human sounds…no slums and no suburbs and no mills and no railway yards…colour everywhere, in the fresh country, in the carven houses, in gilded shrines and flapping banners, in the clothes of people like a covey of varicoloured tropical birds…no din of noise, no pall of smoke, but fresh air blowing within the city and without, even through the narrow streets, none too clean at best, but cleaner far than they were to be thereafter and for many long centuries to come.”

One can forgive Cram for his romanticizing of the high Middle Ages after reading his description of the world he knew from experience, that of the Victorian city, with “dirt, meanness, ugliness everywhere-in the unhappy people no less than in their surroundings.” The long descriptive passage comes from his 1893 novel, The Decadent: Being the Gospel of Inaction. This was actually my first introduction to his writings, and the tale is still vivid in my memory.

But back to the world of 1919:

Are we tempted by the savage and stone-age ravings and ravenings of Bolshevism? Have we any inclination towards that super-imperialism of the pacifist-internatonalist-Israelitish “League of Free Nations” that comes in such questionable shape? Does State Socialism with all its materialistic mechanisms appeal to us? Other alleviation is not offered and in these we can see no encouragement.

And it is here that Cram really gets my attention, with what he describes as the “the eternal dilemma of the Two Alternatives.” He finds this a vicious sophism: “Either you will take this or you must have that.” And this “startling-cry of partizan politics” is the very lifeblood of modern democracies. We see it all the time. Either you are pro-Ukraine or you are a Putin puppet. Either you are pro-Democrat, or you are a Trumpist. Either you must defeat Russia, or you must be subjected to them. These stark binary alternatives are always present in the run-up to war, when the populace must be whipped into a war frenzy.

To this type of thinking, Cram is like a breath of fresh air;

In all human affairs there are never only two alternatives, there is always a third and sometimes more; but this unrecognized alternative never commands that popular leadership which ‘carries the election,’ and it does not appeal to a public that prefers the raw obviousness of the extremes. Yet it is the third alternative that is always the right one, except when the God-made leaders, the time having come for a new upward rush of the vital force in society, put themselves in the vanguard of the new advance and lift the world with them, as it were by main force.

Yes, yes, yes! Take the current Ukraine crisis for example. If, like me, you think that Ukraine checks off more boxes towards being a rogue regime than Russia; and if you think, for example, that the responsibility for beginning the war is about 80% NATO expansion and 20% Russia; and if you think that the responsibility for continuing the war is almost 100% on us, then in this binary world you are merely a Putin puppet, a victim of Russian disinformation; for we all know that our State Department, CIA an NYT would never mislead us. Heaven forfend.

But, if you open you mind, shake off your inbred ideological shackles, then all sorts of “third alternatives” present themselves. Instead of calling for more war, more escalation, more sanctions, it would seem that Kaja Kallas, or Ursula von der Leyen or Kier Starmer or that Danish Prime Minister could get on a jet and go to Moscow and sit down and talk. The Russians have been willing to talk all along. Instead, Europeans are being encouraged to stock up on 72 hours worth of essentials to prepare for an Russian invasion that will never come. Last time I checked—which was this morning—the Russians were crossing the Oskil River, not the Danube. There has to be a third way, rather than waging a war that Europeans have never been able to win before, and which they cannot this time, even with us onboard, which we’ are not. It’s insanity.

Incredibly for 1919, Cram describes the geopolitical world view of the old Atlantic Consensus of 2025:

…an impossible farrago of false values, of loud-mouthed sentimentality and crude, cold-blooded practices; of gross, all-pervading injustice sicklied o'er with the pale cast of smug humanitarianism; a democracy of form that was without ideal or reality in practice; imperialism, materialism and the quantitative standard. Is there no alternative other than this...?

In retrospect, Cram found that progressive evolution-”the nineteenth-century superstition”-to be “defiant of history…responsible in great degree for the many delusions that made the war not only possible but inevitable.” But as the players were sorting out the world at Versailles, Cram took no partisan position.

For my own purpose…it is a matter of indifference which is the victor; in the fight for supremacy; the ultimate issue will be the same though the roads are various. Universal beastliness issuant of Russia, or universal materialism redivivus, the conditions of life will be intolerable, and in the end a new thing will be built up…this status quo ante-civilization or the horror of a recrudescent Bolshevism. In any case, the immediate future is not one to be anticipated with enthusiasm or confidence and we shall do well to consider the course to be followd by those who reject the Two Alternatives and refuse to have any part in either.

I stand with Cram and will look for the Third Way.

A line from “Six Degrees of Separation,” from Stockard Channing’s Ouisa Kittredge to Will Smith’s Paul.

His spelling of Cromwell as “Crumwell” is intentional.

"...he concluded that it must be destroyed so that the ground can be cleared for something better." Echoing the modern theme "Build Back Better" perhaps? The difference is that in the 21st century version, a cabal of oligarchs is trying to "manage" the transition, not to a truly better system, but rather to a system they believe permanently cements their own privilege.

And knowing this, many hang back, resisting the change, because they see the same crappy people who are most responsible for our present dysfunction putting themselves in charge of the change. Those who hang back because they sense the coming of a future dystopia are characterized as being "against progress." We again find ourselves presented with the "two-choice" dilemma.

Likely, the best changes probably need to happen organically, not from some kind of imagined global control room. That may be the one thing that makes today different--in past societies, planned changes were just not possible on a global scale.

Great piece!

Crumwell, intentional! Love this guy. A life without YouTube, Tik Tok and other various mind leeches, is potential for endless learning and retrospect. Thanks Terry. Once again, a discovery of fresh fodder for the soul.